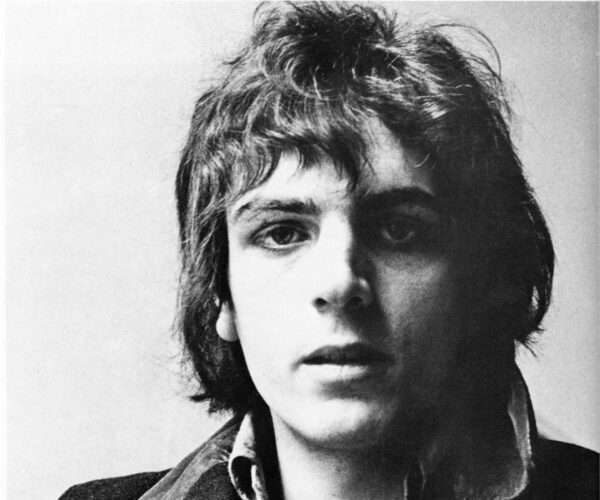

A Panegyric to Syd Barrett

The story of Syd Barrett is a perfect example of how not to live your life if you want a lasting career in show business. But then again, Barrett’s life never had anything to do with business. Everything that he created was marked by a distinct stamp of total disregard for commercial success. The fact that royalties from the first two Pink Floyd albums allowed him to live a comfortable life after his withdrawal from the scene, was a mere side-effect of his fragile talent, which has always had a supremely introverted quality to it, devoid not only of any desire to write a hit, but also from any wish to pay attention to the potential or actual audience.

Barrett plainly wasn’t much interested in the response that his music produced. Even at the time when he was in sound mental health, archive footages of his performances with Pink Floyd show that he was barely noticing the crowd. An explanation of this attitude is odd but not far-fetched – Barrett wasn’t a crowd-pleaser not because of some consciously assumed high moral stance, but because he had an indulgent personality and sought the pleasure of expressing his thoughts and feelings in music ( as accurately as his somewhat limited technical skills allowed him) solely for the sheer enjoyment of articulating them, having no interest in connecting with the audience and expecting no particular response.

‘Piper at the Gates of Dawn’, the first Pink Floyd album for which Barrett wrote 10 out of 11 tracks, shows how he took exactly as much time as he decided was necessary to explore his ideas. ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ is a perfect example of this approach. This track goes beyond self-indulgence. It is meticulously explorative to the point of resembling a research into music theory. The paradox and magic of this music is that, while being almost pedantic, it manages to remain touchingly beautiful.

Barrett’s music was fragile and introvert but it wasn’t unhappy. Sometimes it was sad, sometimes light-hearted and humorous, sometimes it took him to places within himself which were outlandish and chaotic, but it never had the heavy, despairing quality of later Pink Floyd albums like ‘The Wall’ and ‘Animals’. In a way, even when suffering from his illness, Barrett was intrinsically a more content person than his ex- bandmates David Gilmour and Roger Waters. Barrett didn’t torment himself purposefully in order to produce ‘deeper’ music. His schizophrenia tormented him and Barrett wasn’t a willing victim of his illness.

After Pink Floyd fired him in 1968 due to his escalating erratic behaviour, Barrett became a text-book example of an extremely talented musician who lost his career to drugs. He lost not only his career, but his desire to be involved in the music scene. His two solo albums, ‘Madcap Laughs’ and ‘Barrett’, both released in 1970 and produced by David Gilmour and Roger Waters, emerged as a result of an eager interest on the part of EMI and mostly featured material which Barrett wrote in 1966-1967. These two albums break down distinctions between Barrett’s life and his art and show that anything that went on in his life could be relevant to his music.

Throughout their career Pink Floyd preserved a lot of Barrett’s spirit which he introduced to the band during its formative years. Like Barrett, they remained self-confessed nonconformists, their music describing the isolated, solitary existence of a social misfit. David Gilmour, either consciously or unconsciously, chose to sustain Barrett’s minimalist approach to guitar technique in spite of his obvious ability which had a potential to develop in many different directions. It is never clear if this band’s anguish and dejection was a direct result of the trauma of losing Barrett or if it had deeper roots in their own dark vision of the world we live in. It could be both, but the theme of a lost friend, of an institution, of confinement, imprisonment and solitude recurred in their work over and over again.

Barrett never returned to music properly after he left Pink Floyd and he never realised his full potential. The drugs which he was taking excessively before his already fragile mental health collapsed, took away from him what many at the time believed they were capable of enhancing: creative energy and a will to explore. We will never know how much of the revelations contained in the first two Pink Floyd albums, owe their innovative quality to drugs, how much to Barrett’s unique talent and how much to the boldness and the pioneering spirit of the late 60s.

What we do know is that ‘Piper at the Gates of Dawn’ and ‘Saucerful of Secrets’ have proved to be the most advanced albums that Pink Floyd have ever recorded. In a way these works proved to be too innovative and too progressive and once Barrett left, the band retreated to the safer ground of more traditional forms of expression. The new dimension in music discovered by Barrett, however, did not only lead other bands to explore the boundaries of creativity but became one of the best and most vivid illustrations of that extraordinarily inspired time in the history of music – the late 1960s. Of all musicians of this vanguard, Barrett was the purest – liberated from value, vanity or fear of the unknown.

Guest article from Alyssa O.

Written by Guest Writers on